Dr. Leo Twiggs

PAYING TRIBUTE

by Stacy Huggins

“When I began to do this, I was not thinking about doing nine paintings,” says Dr. Leo Twiggs.

A long-time friend and supporter of Twiggs’s work encouraged him to expand on a painting he had made in response to the June 2015 tragedy at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. That horrifying night, nine parishioners, including the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, were brutally gunned down in a Wednesday night Bible study.

Twiggs also attends Bible study every Wednesday. He describes it as an intimate study of the Bible with their pastor, accessible and immediate. “It was like the whole Bible Study was taken away.”

“I tried to concentrate on the nine people that died. That’s why it is called Requiem… ‘requiem’ is about a funeral. By concentrating on it, I thought about the Christian tradition, and how important Christianity has been to African Americans.

When African Americans first came to this country “they were converted to Christianity, and they took their Christianity seriously, because when you have slaves coming over to a new country…you erase their history and they’re drifting along, they have to have something to hold on to, and they took Christianity as that thing to hold on to.”

“It struck me how important Christianity was…in Charleston when DuBose Heyward wrote [his novel Porgy, the basis for the opera Porgy and Bess] in the 1920s. It was the same kind of heritage of Christianity that came up through Mother Emanuel.”

During the blockbuster performance of Porgy and Bess at Spoleto Festival USA, Twiggs noted with interest how the spire of Mother Emanuel and other churches were visible in the set throughout. Central characters Crown, Sportin’ Life were “blasphemous, and Bess was immoral,” while Porgy and the remainder of the cast were very religious. Twiggs sees parallels in the play to the Mother Emanuel congregation’s dedication to God.

His nine paintings are not sequential. “It’s a testimony to the moment,” he says.

His nine paintings are not sequential. “It’s a testimony to the moment,” he says.

Twiggs recalled attending church service with his mother, where parishioners “would testify about what God had done for them, and then they’d sing a song. It was free to anybody; any member could do that. But you can’t testify unless you’ve had a test.”

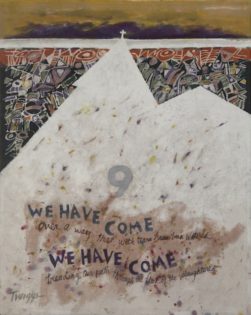

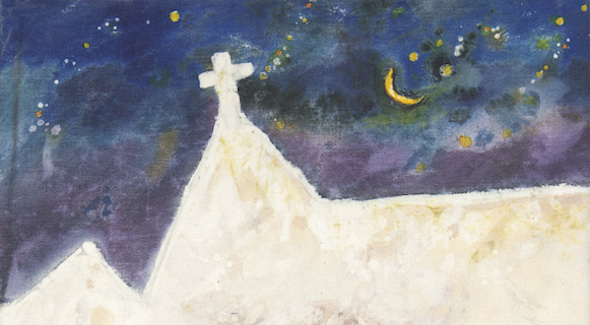

As the series developed, Twiggs drained the color from the Confederate Flag, which begins as a bloody, crimson stain on the pure white church that represents Mother Emanuel. Each painting slowly drains the red from the tattered, bloody flag, taking the power away from an obsolete symbol that was appropriated to commit this heinous crime. The X of the flag morphs into a cross, and the palmetto flag, the ubiquitous symbol of South Carolina, creeps into the background as nine X’s shift on their axes into crosses.

The final paintings pay tribute to the ascension of the nine from this pedestrian condition to the Heavenly realm, and to their African heritage through the vibrant patterns and colors of the church’s stunning stained glass window and the funerary clothing worn by the pastors and bishops during the memorials. The jewel-toned blues and greens were breathtaking, reminding Twiggs of the ritual clothing of African royalty.

“What happened at Mother Emanuel is not unique to Mother Emanuel…it is the ‘stony road we trod’.” Twiggs emblazoned two other lines from “Lift Every Voice and Sing” by John Rosamond Johnson on his ninth and final painting.

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

“I grew up in segregation. I grew up in Jim Crow. I’ve seen the transition, and in my paintings, I can’t divorce myself from that…but you can’t be an angry painter. You have to see how you can use your art to be enlightening,” says Twiggs.

“This Mother Emanuel series, it was difficult, but it was something I had to do.”

“It’s good to do it at this time in my career because I could bring maturity to it that I couldn’t have early on.” In his early days,  Twiggs spent so much time just mastering his medium, the ancient art of batik, where wax resists are used to leave negative spaces as he paints around them. Unlike painting, the dyes and paints merge and meld with the fabric, and as colors layer on top of another they affect the colors beneath them. It is an unforgiving art form that took him years to master. His use of the Confederate Flag and target imagery dates back to the 1970s. Twiggs’s Requiem for Mother Emanuel is the most significant tribute to date.

Twiggs spent so much time just mastering his medium, the ancient art of batik, where wax resists are used to leave negative spaces as he paints around them. Unlike painting, the dyes and paints merge and meld with the fabric, and as colors layer on top of another they affect the colors beneath them. It is an unforgiving art form that took him years to master. His use of the Confederate Flag and target imagery dates back to the 1970s. Twiggs’s Requiem for Mother Emanuel is the most significant tribute to date.

As Requiem hangs at the City Gallery, viewers will likely find themselves challenged by the imagery, but nothing about this healing process will be easy. As Twiggs says, it is difficult, but it is something we have to do.

Requiem For Mother Emanuel

Currently on view through February 19, 2017

THE MINT M– USEUM

2730 Randolph Road, Charlotte NC

Leo Twiggs is represented at

Hampton III Gallery, Greenville SC

and

if ART Gallery, Columbia SC

Visual Artists Profile

Sussan Sanavandi: A Color Story

Visual Profile

Growing the Arts in North Charleston

Collectors Series

The Home of David Boatwright & Molly B. Right

Comments (0)

No comments yet

The comments are closed.